When people in heteronormative relationships decide to come out, they are lauded for their bravery. But what happens to their partners they leave behind?

At the beginning of 2020, Diana was feeling happy. Her eldest son was at university and her other two children weren’t far behind him. Her husband was approaching retirement from the company where he’d climbed the corporate ladder. Together, they’d started planning what they were going to do when he stopped working. Top of the list was buying a campervan and travelling around the UK and into Europe too, maybe. “It felt like the end of the difficult years,” she says.

Diana had been with her husband since she was 16. The first time they met, she had snuck into a pub where she knew they’d serve her, even though she was underage. As she walked into the bar, she saw him with a group of friends and knew that she fancied him. “I went home that night and I said to my mum, ‘I’ve met the man I’m going to marry’. It’s embarrassing, but it’s true.”

They officially became a couple two years later and stayed together for the next 42 years. “It was a brilliant relationship; we laughed every day.” When she describes their time together, Diana paints the idyllic suburban coupling. Of course, there were ups and downs, but the fundamentals were there – great kids, a close extended family, a lively social life, holidays abroad. “I adored him.”

“I can remember saying to him, ‘I don’t understand’, and I was clutching his hand. I felt almost transported, I felt numb, I couldn’t gather my thoughts”

One morning, Diana woke up in bed with her husband. The night before, they’d been to a party, and Diana had thought that her husband seemed off but didn’t take too much notice of it. As they sat in bed with their cups of tea, they chatted about their evening and their kids, and then Diana asked her husband if he’d heard about Phillip Schofield, who had come out on national television the previous day, revealing that he’d separated from his wife of 27 years.

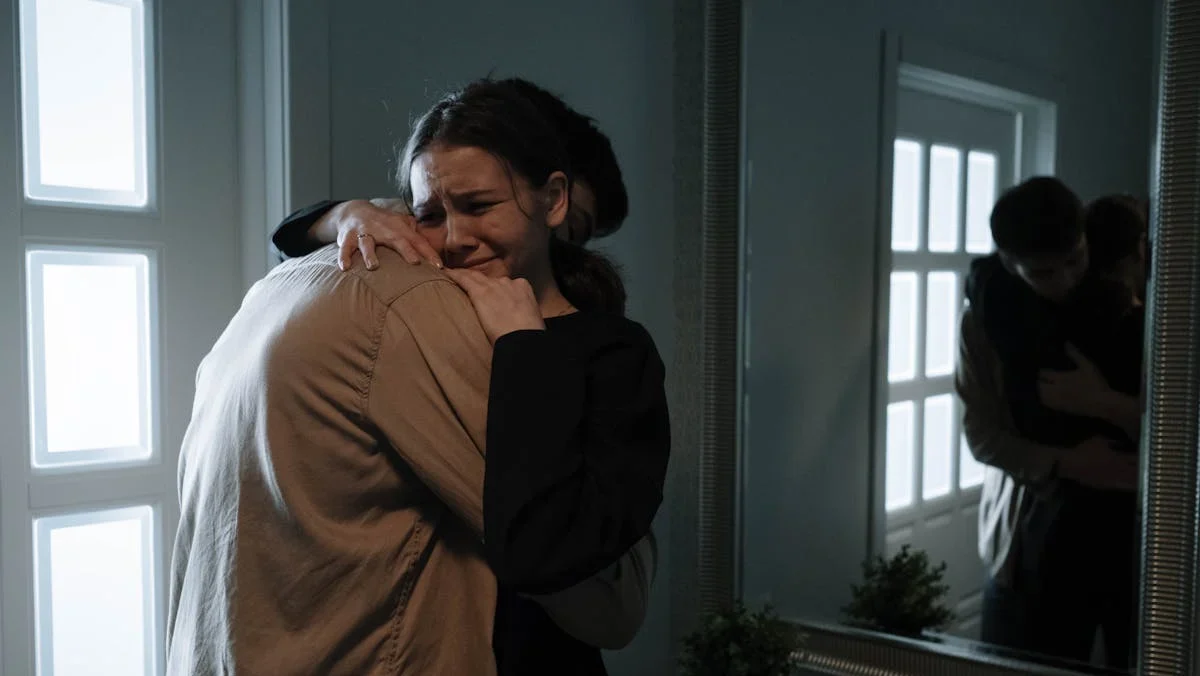

As soon as she brought this up, her husband’s demeanour shifted, and he turned to her and said that there was something he was struggling with – his sexuality. “I can remember I started crying,” Diana recalls. “I can remember saying to him, ‘I don’t understand’, and I was clutching his hand. I felt almost transported, I felt numb, I couldn’t gather my thoughts.”

In conversations over the following weeks and months, Diana’s husband revealed to her that he’d experienced attraction to men since he was a teenager and that he was questioning his sexuality before finally revealing that he was gay. “It was like a death – it was a bereavement to me. It was like my whole experience of life up to that point had been a lie.”

Diana’s experience is shared by tens of thousands of other women across the world, whose often happy and fulfilling lives have been devastated in the wake of their partners coming out. And while their partners are celebrated for discovering their true selves, they’re left to pick up the pieces of their lives. This experience leaves women feeling lost in the shadows of their partner’s coming out – unable to find adequate support and often left to navigate their trauma alone.

As society has moved to accept queer men more readily, the experience of coming out has changed. When Schofield came out on national television, the country’s immediate reaction was to praise him, but for women who’d experienced a relationship like this the reality is more complex. Olivia was married for seven years before her husband came out and remembers watching Schofield speaking on This Morning: “I’m thinking behind all that is a woman who I know from personal experience is on the floor, having to think about breathing in and out because she’s in so much pain.”

Women are often forced into the position of outwardly supporting even though their lives have been upended and don’t receive the same kind of support as during other breakups.

“She’s not like a widow, where people are giving her sympathy and flowers and casseroles. She’s supposed to be happy for him while she’s a bereaved wife,” says Karen Bieman, who founded Not My Closet, a counselling service for straight men and women who’ve discovered that their partner is gay.

Bieman’s desire to help came from her personal experience. After being married to her husband for decades and having five children together, her partner came out. Bieman had just moved cities all the way across Australia and didn’t have a support system in her new home. “I didn’t know who to talk to,” she says. “I couldn’t talk to anybody because I was worried about the response.”

Initially, Bieman turned to social media. Self-organising groups have formed across platforms like Facebook and Reddit as places for straight spouses to connect. Although people find power in connecting, in reality, those groups can be difficult to navigate. “You’ve got a lot of wounded people in one space, and it’s not moderated. There’s a lot of rage, and people can get quite triggered,” says Bieman. “It’s easy to get re-traumatised.”

“It’s like a house built on sand instead of rock; the foundations are wrong”

After her own experiences, Bieman didn’t want any other person to go through this without a support system, and so years later, she decided to start counselling other women. “They will often come and say, I finally feel like someone gets it.”

Bieman has now worked with women from across the world for the last five years. While every relationship and every coming out is different, Bieman has seen some commonalities in women’s experiences that she describes as the stages of healing.

The initial reaction for most women is that of shock. “They’re completely blindsided,” says Bieman. Many of the women that she has worked with believed they had good, healthy relationships, and this immediately shifted their world. This can be particularly hard, as even though this is new information to them, their partner has known for a long time. “The straight spouse is at the very beginning of their processing,” says Bieman. “But their partner has been processing this for some time. They are ready to come out.”

After shock comes an intense period of self-doubt. “You pick back over everything and look for the signs that you missed,” says Carolyn. The emotions in this stage can be intense, as the person the straight spouse has been closest to in their lives is revealed to have hidden a secret. The feeling of being lied to is palpable, but so are the feelings of shame and embarrassment. Questions immediately rise to the surface: how was I so convincingly deceived? Was I the only one who didn’t know? Do people think I’m stupid?

At the same time, women are reckoning with the legacy of their relationships. “It’s the death of everything you thought you had,” says Linda, whose partner came out weeks after their tenth anniversary. “It’s not that it’s not true, but it’s like a house built on sand instead of rock; the foundations are wrong.”

Straight spouses have to recontextualise all of their memories, as every happy moment is tinged with a reality that lies beneath the surface. “I found it very difficult to look back at when my children were small and at all the family photos I have,” says Diana. This leaves many women trying to figure out what was “real” in their relationship, trying to ascertain the truth that existed within their partner’s deception.

Bieman recommends the way that women do this is to picture their life as though it’s a line. Above the line is the reality of the life you lived: mornings in the kitchen, holidays abroad, nights on the sofa, and below the line is an area that you didn’t know about. But even though that area exists, it shouldn’t negate the happy memories: “Even though there was a part of him that he was keeping hidden, she was living authentically, and she should remember that,” says Bieman.

Intrinsically tied to the feeling of self-doubt is the feeling of betrayal. Although not necessarily malicious, when a partner hides their sexuality, it is a deception – that straight spouses can feel like they were forced to participate in. “You live a lie that you haven’t chosen, and you didn’t know about,” says Linda. “If you choose to live a lie, that’s ok, that’s your choice – but I didn’t get to choose”.

For Bieman, though, the hardest stage that straight spouses travel through is grief. Whereas traditional grief looks forward to the future that will never be, the grief of a coming out can feel omnidirectional. “They’re grieving the past, as well as the now. There’s a grief of the lost future and of the lost years, the years that didn’t happen. There’s a grief for the life they didn’t have.”

“I decided very early on I just wasn’t going to be defined by it. I didn’t want my identity to be the woman who married a gay man”

This grief leaves many women feeling like their lives were taken from them, which is often a fraught point as they navigate the end of their relationships. After her partner came out, Diana remembers a conversation in which she told him that he’d stolen her life. “He was incredulous. He said: ‘I’ve provided for you. I’ve been a good dad to the kids. I’ve done this, I’ve done that.’ But it’s a lie.”

And while many women had the life that they envisaged, this grief is particularly hard for those whose relationships didn’t fulfil all their needs. From when she was a young woman, Linda had always wanted to be a mother: “I was so broody. I used to dream that I was pregnant, dream that I was giving birth. If I had as many kids as I did in my dreams, I’d be like the old woman who lived in the shoe”. Linda’s partner didn’t want to have children, though, and by the time he came out to her, she felt it was too late to become a mother.

“They’ve stolen everything you’ve ever dreamed of, everything you’d hoped for. When you get married, you have a dream of your future – you think you’ll be together, you think you’ll have kids, grandkids,” says Olivia. “If I hadn’t married him, maybe I would have met someone else, maybe I would have had a family.”

But even as their lives are being turned upside down, it can still be hard for women to process their pain. “Women are typically socialised to be nurturers, caretakers,” says Bieman. “When this happens in a relationship, it can feel unnatural for a woman to go against her natural instincts and actually turn away from all of that and go, ‘my feelings actually matter here as well’.”

During her time counselling, Bieman observed the specific ways that gender had affected her client’s experiences. Most of the women she has worked with were the primary caregivers to their families and, as a result, have strong instincts to keep their families protected, which can lead to some women becoming “adaptive and accommodating to their partners, attending to him and caring to the kids – but often at a real loss to her.”

It’s because of this that Bieman believes the most important thing for women to remember is that their experiences are valid. “It’s okay to be angry even if he’s gay, you can be angry about what you’re going through. You were right to feel like this situation is tough.”

While this experience can have devastating effects in the short term, every woman who experienced this has found ways to reorient their life. Jessica was married to her husband for 26 years before he came out. As she processed her initial shock, she made a commitment. “I decided very early on I just wasn’t going to be defined by it. I didn’t want my identity to be the woman who married a gay man.”

For the past few years, she’s processed her husband’s revelation and has even met other women who’ve shared her experience through the organisation Straight Partners Anonymous. Although what she went through felt overwhelming at first, she’s now at the point where she can provide support to others and has one piece of advice she always provides: “In five years’ time, you won’t believe where you’ll be. You’ll have built yourself back up, and you’ll have put yourself right at the centre.”