Finn Cliff Hodges chats all things Bee Gees and breakups with bona fide Bee Gees brainiac Bob Stanley

The best band to come out of Manchester: The Smiths? Joy Division? New Order? The Stone Roses?

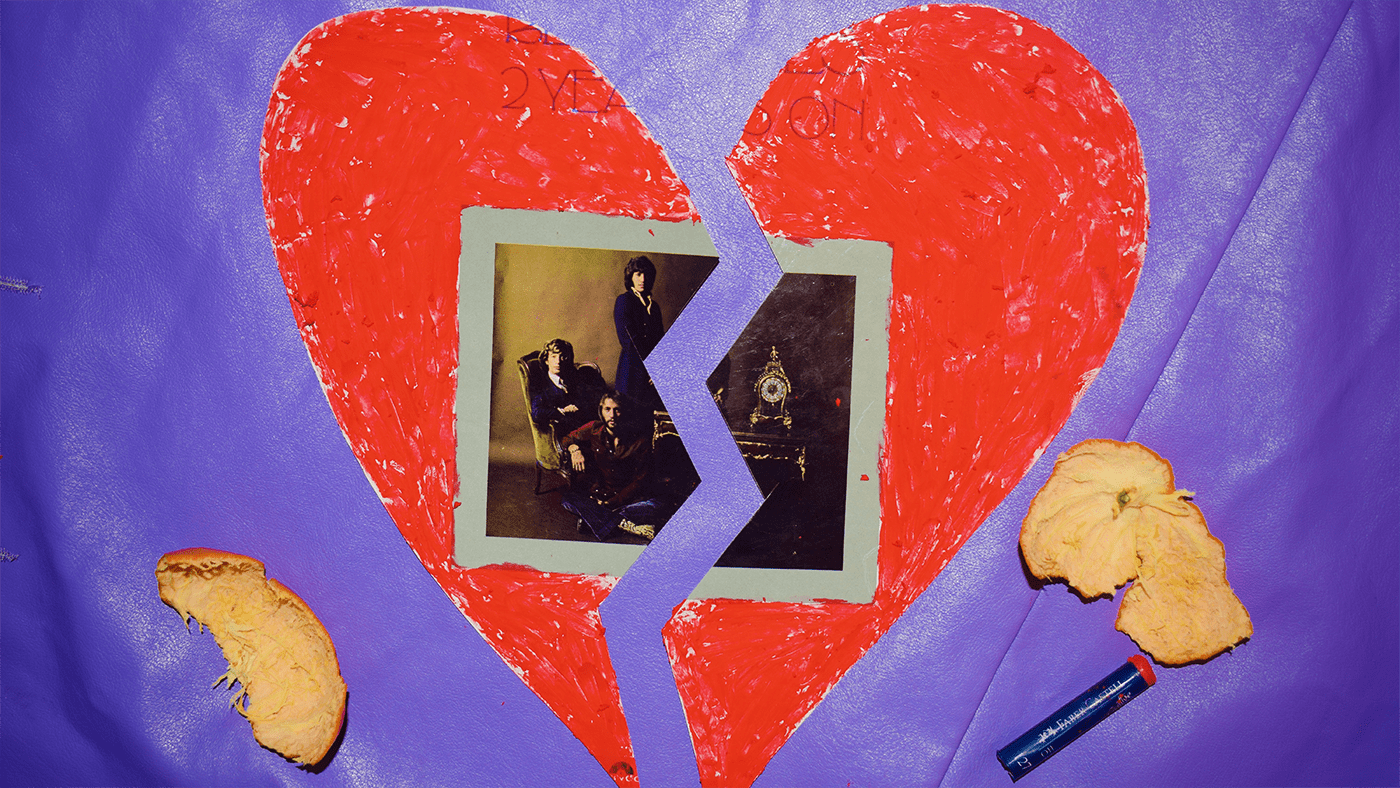

Some might argue it’s the Bee Gees, others may not even know that Barry, Robin and Maurice launched their long career at The Gaumont in the Manchester suburb of Chorlton-cum-Hardy as The Rattlesnakes. They were a band of troublesome kids who had frequent run-ins with the police for theft and arson – unsupervised by their busy parents and never far from ending up in borstal.

But beyond the flamboyant outfits and ethereal vocals lies a tortured core of three songwriters who crafted some of the most exquisite heartbroken ballads in pop history, their genius lying in the weaving of deep sorrow into shimmering melodies.

The Ultimate Heartbreak Anthem

So, how exactly do you mend a broken heart the Bee Gees way? Surely, the Gibb trio all want to be saved from the relentless heartache they have expressed throughout their 50-year songwriting career. You would hope that a saving grace might be found in the very track that asks that question outright.

How Can You Mend a Broken Heart? was the Bee Gees’ first US number one in 1971 and appeared on the album Trafalgar. Though the original version may be overlooked by the devastatingly beautiful Al Green cover, which has no doubt conjured countless tears, the original is not only a perfect example of a pop ballad but also of the brothers’ peerless compositional skills.

The song is a demonstration of heartbreak between brothers; brothers mourning the loss of their band. Robin and Barry pour out their existential despair at a world that has turned strange and unfair, pining: “How can you stop the rain from falling down? / How can you stop the sun from shining?” before transitioning to a personal plea:

“How can you mend this broken man?

How can a loser ever win?

Please help me mend my broken heart and let me live again.”

The harmony of the Gibb brothers’ sheep-like bleating as they crescendo into the chorus mimics an overwhelming feeling of sadness and bewilderment, like a voice about to break down. And when the chorus does arrive, a gentle “and” is sung as the acoustic guitar slowly strums and the orchestration in the background swells and dips, echoing the tiredness of this heartache, the strain, before asking the earnest question of the song’s title but never quite giving an answer.

Beyond the flamboyant outfits and ethereal vocals lies a tortured core of three songwriters who crafted some of the most exquisite heartbroken ballads in pop history

The Power of Sadness

Bob Stanley, author of the definitive Bee Gees: Children of the World, cites it as one of the Bee Gees’ most on-the-nose songs: “It’s very simple, it’s very soulful,” he says. “Its message is more direct than a lot of their songs. One of the reasons I wrote my book was to correct these knee-jerk reactions. If you can’t hear that the song isn’t meant to be affecting and emotional, then you’re just not listening properly.”

However, Stanley’s award for the most powerful heartbreak song goes to I Can’t See Nobody, which Robin Gibb wrote at age 17: “You feel any themes of heartbreak more intensely at that age, in more of an abstract way than you do when you’re older.”

Just two years later, Robin was giving haunting vocal performances on songs like Down to Earth, conveying the experience of heartbreak through the actual production of the vocals. “Robin literally sounds like someone isolated in a bubble floating in space. It’s an incredibly desolate, strange-sounding production,” Stanley observes.

The Production of Heartbreak

The brothers’ isolated vocals are not a production technique they utilised for just one song. In the poignant Someone Belonging to Someone, the reverb plastered onto their falsetto adlibs and vocals adds an air of loneliness, of heartache and pain, and shows how even their production choices contribute to the overarching theme of heartbreak in their music. Yet, despite the sadness echoed throughout their music and society’s addiction to listening to sad music, Stanley reveals a surprising secret: “I don’t think they’ve ever gotten me through a tough period.”

The epitome of Bee Gees’ music lies in this deception. If you weren’t reading the lyrics or researching their history, it would be easy to brush their music off as simple 70s or 80s pop produced by satin-jacketed, medallion-touting, stunningly uncool young mannequins. In doing so, you would fail to acknowledge these songs’ palpable depth and ability to create things of beauty from the detritus of loss, loneliness and heartbreak.